In this episode of Meaningful Work Matters, Andrew Soren spoke with Jeff Thompson, Director of the Sorensen Center for Moral and Ethical Leadership at BYU, where he has also been a professor for over 20 years. Jeff’s calling in life is to assist people in discovering and pursuing their own sense of calling, and his work focuses on meaningful work, particularly in health care.

Thompson has spent his career researching how individuals discover a sense of calling in their work, which he came to through his work helping to make physicians feel valued at work, as well as understanding why medical professionals struggle to work for corporate entities. Ultimately, he is passionate about ensuring that organizations feel safe and that people can express their values at work.

Discovering a Calling

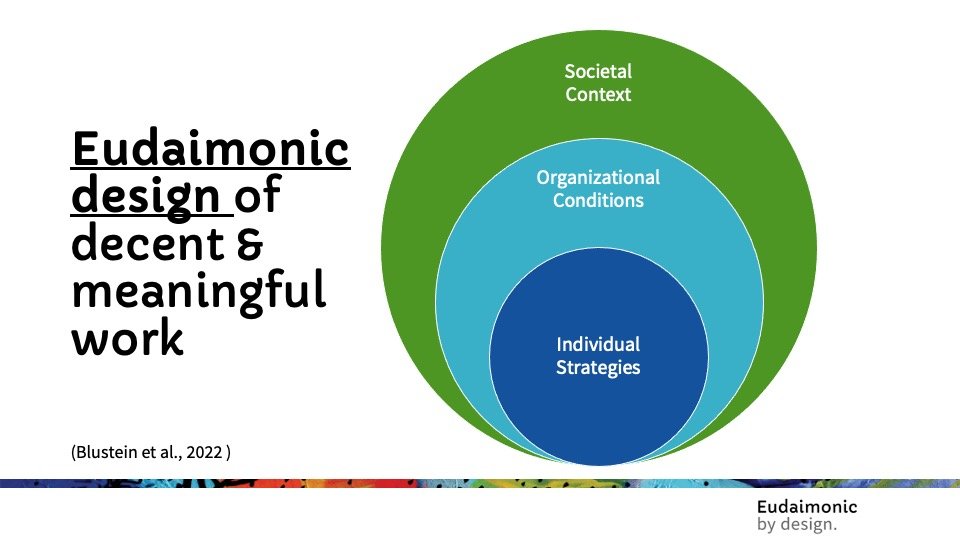

Thompson offers a nuanced definition of a calling, describing it as the intersection of one's natural talents, passions, and a sense of purpose that beckons them. He emphasizes the importance of passion, purpose, and place in defining a calling, drawing parallels to eudaimonic theories of meaningful work.

The idea of a calling can be traced throughout history, finding its roots with Martin Luther in the Protestant Reformation. Prior to Luther's time, work was often viewed as mundane or even burdensome, but Luther introduced the notion that work could be a noble endeavor, a partnership with God to bless humanity. This transformed the perception of work, imbuing it with a sense of purpose and dignity. The term "calling" emerged from this religious context but has since become secularized, with individuals from diverse backgrounds seeking meaningful work experiences.

There are some contemporary challenges with the idea of a calling, as Thompson explains, noting that while there is a widespread desire for meaningful work, there is often ambiguity about who or what is doing the calling. This ambiguity may lead to a sense of entitlement to a fulfilling career without a clear understanding of its origins or implications.

The Popularity of Meaningful Work

In recent years, Thompson says, there has been a surge in interest in meaningful work and finding a calling, especially among students. Thompson explains that, as an educator, he has observed a shift in students' aspirations towards finding meaningful work. He notes a growing desire among individuals to feel valued and make a meaningful contribution, reflecting an inherent human urge to matter in society.

Transcendent Calling

Thompson also explores the idea of a "transcendent calling," as discussed in a recent article he co-authored with Stuart Bunderson.

Drawing inspiration from Abraham Maslow's theory of self-transcendence, the idea proposes that a transcendent calling occurs when an individual's inner passion aligns with an external purpose or societal need. This alignment represents the pinnacle of motivation and fulfillment, bridging personal fulfillment with broader societal contribution.

Thompson’s own studies reflect this theory, particularly one on zookeepers, which challenged stereotypes about their profession. Despite low pay and challenging working conditions, zookeepers expressed a profound sense of calling and dedication to their work. This dedication stemmed from their passion for animals and their belief in the importance of their role in conservation efforts.

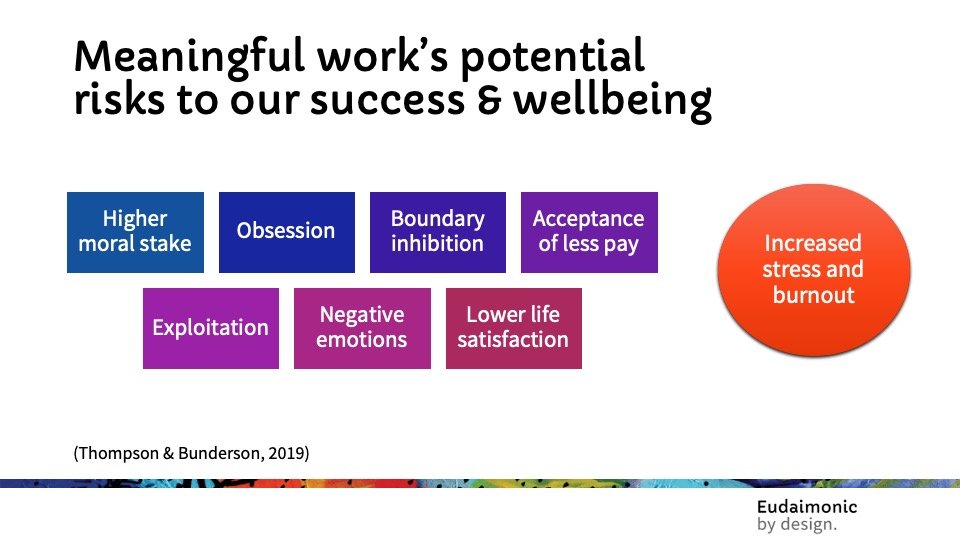

Exploitation in the Workplace

Through this research, Thompson also discovered the idea of “commitment camouflaging”, where employees hide their dedication to avoid exploitation by management.

Thompson says that many people will find value in their work, despite challenging circumstances. Even the jobs that seem the most menial can be imbued with purpose and meaning.

Teachers are among those professionals who often face significant exploitation in the workplace, but many remain committed to their calling due to the importance of their work. According to Thompson, individuals may be able to mitigate the negative effects of such exploitation if they feel a profound sense of calling.

Leadership and a Sense of Calling

Thompson emphasizes the concept of dignity, which highlights the infinite worth of individuals and the importance of recognizing their contributions, especially in the workplace. He suggests that leaders should remain aware of their employees’ desire to find a calling, and they should view that quest as noble.

Therefore, they should strive to honor, reward, and respect that endeavor accordingly for all employees.

Thompson provides a number of ways to put this into practice, including expressing gratitude, offering opportunities for initiative and growth, and fostering a sense of community among like-minded individuals.

Final Thoughts

All employees should feel that their work is respected and their desire for a greater purpose is understood. For anyone who feels their calling is not recognized, Thompson advises seeking support from peers.

He also urges every person to understand that there are risks to the search for a calling, as leaning too far into that desire can cause a severe moral burden that is hard to emerge from.

Meaning is inherently existential in nature and, therefore, it can be difficult to find. It is likely an ongoing quest that will last a lifetime.